Extrapolation to graphene surface

A main result of H2 PAHs series of calculations (shown on Fig. 2.1) is the presence of a correlation between the number of the hexagonal carbon rings and the H2

PAHs series of calculations (shown on Fig. 2.1) is the presence of a correlation between the number of the hexagonal carbon rings and the H2 PAH interaction (see Table 2.2).

In other words the interaction grows with the number of the closely situated hexagon rings.

For the H2

PAH interaction (see Table 2.2).

In other words the interaction grows with the number of the closely situated hexagon rings.

For the H2 benzene complex, the physisorption energy is found to be 4.8 kJ

benzene complex, the physisorption energy is found to be 4.8 kJ mol

mol , while for the central ring of coronene it is 6.4 kJ

, while for the central ring of coronene it is 6.4 kJ mol

mol .

All other sites studied here give physisorption energies between these values.

Moreover, these series of calculations show that the interaction increases with the size of the PAH.

On the other hand, a ring situated at larger distance contributes less to the total H2

.

All other sites studied here give physisorption energies between these values.

Moreover, these series of calculations show that the interaction increases with the size of the PAH.

On the other hand, a ring situated at larger distance contributes less to the total H2 PAH energy interaction.

The latter effect can be clearly observed by changing the adsorption site (ring) of H2 on linear PAH molecules like naphthalene, anthracene and pentacene (see Tab. 2.2).

1.0

PAH energy interaction.

The latter effect can be clearly observed by changing the adsorption site (ring) of H2 on linear PAH molecules like naphthalene, anthracene and pentacene (see Tab. 2.2).

1.0

A comparison with DFT and related Kohn-Sham of constrained electronic densities (KSCED) computations shows a contradiction

(see Table 2.3).

The detailed study of the H2 PAH interaction by Tran et al. [52] shows that there is an attractive interaction caused by

weakly overlapping densities.

The interaction energies are slowly varying between at 3.8 and 4.9 kJ

PAH interaction by Tran et al. [52] shows that there is an attractive interaction caused by

weakly overlapping densities.

The interaction energies are slowly varying between at 3.8 and 4.9 kJ mol

mol , but they are not size-dependend within KSCED and DFT.

This is because the available implementations of these theories to present-day are restricted by exchange-correlation functionals which do not include the dispersion interaction properly.

, but they are not size-dependend within KSCED and DFT.

This is because the available implementations of these theories to present-day are restricted by exchange-correlation functionals which do not include the dispersion interaction properly.

The reported BSSE corrected PW91/6-311++G** and KSCED/TZVP studies [52] show a roughly constant interaction energy, independent on the system size.

Although, the reported PW91/6-311++G** and KSCED/TZVP interaction energies[52] are PAH-size independent , they are in the correct order of magnitude.

An important fact is that better agreement is found for the results of smaller PAHs (i.e. benzene, naphthalene), while the H2 interaction with large PAHs is underestimated.

Additionally, the H2 benzene interaction within these methods is even stronger than for some larger PAHs, which is in contradiction to the MP2 results.

This can be easily understood if one consider a missing long-range part of the energy interaction.

In contrast to GGA-DFT, the hybrid B3LYP/cc-pVTZ calculations show the correct trend, however, they strongly underestimate the interaction energy.

Hence the KSCED and DFT methods give us information for the attractive abilities of the adsorption site itself.

Combining that information with the MP2 calculations it can be stated that the physisorption energy depends not only on the size of the PAH, but also on the H2 adsorption site of the molecule.

Thus the stronger interaction with the non-central rings of triphenylene (see Table 2.2) can be explained with their stronger attraction capabilities due to a reorganisation of the electron

benzene interaction within these methods is even stronger than for some larger PAHs, which is in contradiction to the MP2 results.

This can be easily understood if one consider a missing long-range part of the energy interaction.

In contrast to GGA-DFT, the hybrid B3LYP/cc-pVTZ calculations show the correct trend, however, they strongly underestimate the interaction energy.

Hence the KSCED and DFT methods give us information for the attractive abilities of the adsorption site itself.

Combining that information with the MP2 calculations it can be stated that the physisorption energy depends not only on the size of the PAH, but also on the H2 adsorption site of the molecule.

Thus the stronger interaction with the non-central rings of triphenylene (see Table 2.2) can be explained with their stronger attraction capabilities due to a reorganisation of the electron  -system.

However, physisorption sites such as in triphenylene are considered to be only typical for the edge of a graphene structure.

If no defects are considered, their contribution to the H2

-system.

However, physisorption sites such as in triphenylene are considered to be only typical for the edge of a graphene structure.

If no defects are considered, their contribution to the H2 graphene interaction energy will vanish far from the edges since the properties of the structure become uniform.

Therefore triphenylene, which has a quite special topology compared to the other PAHs, can be excluded form the H2

graphene interaction energy will vanish far from the edges since the properties of the structure become uniform.

Therefore triphenylene, which has a quite special topology compared to the other PAHs, can be excluded form the H2 PAHs series.

Thus, considering only the highest H2

PAHs series.

Thus, considering only the highest H2 PAHs interaction energies, a general trend can be observed:

The more neighbouring rings the adsorption site has the stronger is its interaction.

On the other hand sites with identical number and position of first neighbours have very similar interaction energies.

In particular, the outer rings of naphthalene, anthracene and pentacene, all having only one neighbour ring, differ by not more then 0.03 kJ

PAHs interaction energies, a general trend can be observed:

The more neighbouring rings the adsorption site has the stronger is its interaction.

On the other hand sites with identical number and position of first neighbours have very similar interaction energies.

In particular, the outer rings of naphthalene, anthracene and pentacene, all having only one neighbour ring, differ by not more then 0.03 kJ mol

mol . (see Table 2.2)

The central ring of anthracene and the second ring of pentacene, both having two neighbours at the same positions, differ by 0.1 kJ

. (see Table 2.2)

The central ring of anthracene and the second ring of pentacene, both having two neighbours at the same positions, differ by 0.1 kJ mol

mol .

Moreover in Table 2.2 it can be seen that physisorption energy converges against a saturation for a linear chain of rings (benzene, anthracene, pentacene).

Thus central site of coronene has a physisorption energy of 6.39 kJ

.

Moreover in Table 2.2 it can be seen that physisorption energy converges against a saturation for a linear chain of rings (benzene, anthracene, pentacene).

Thus central site of coronene has a physisorption energy of 6.39 kJ mol

mol , which is expected to be slightly weaker than the interaction

energy of H2 with graphene.

This indicates that H2-PAH interaction approaches a limit with increasing size of the PAH size, which is the H2-graphene (PAH with infinite size) interaction energy.

So far it can be assumed that trends found for small PAHs holds as well for larger ones, in particular for those which are contiguous or have a convex shape, like the nano-scale graphene platelets.

This way the physisorption energy of a H2 molecule, adsorbed perpendicular to the sheet on top of a ring centre, at a distance 3.1 Å between PAH sheet and H2 centre, can be estimated by a simple equation.

This can be motivated by the following facts:

, which is expected to be slightly weaker than the interaction

energy of H2 with graphene.

This indicates that H2-PAH interaction approaches a limit with increasing size of the PAH size, which is the H2-graphene (PAH with infinite size) interaction energy.

So far it can be assumed that trends found for small PAHs holds as well for larger ones, in particular for those which are contiguous or have a convex shape, like the nano-scale graphene platelets.

This way the physisorption energy of a H2 molecule, adsorbed perpendicular to the sheet on top of a ring centre, at a distance 3.1 Å between PAH sheet and H2 centre, can be estimated by a simple equation.

This can be motivated by the following facts:

- (i) DFT and KSCED computations give a nearly constant interaction of H2 and PAHs, independent on the PAH size from benzene

to ovalene [52].

- (ii) Full geometry optimisations at the MP2/cc-pVTZ level for H2 adsorbed at the central positions of I, II, and III indicate that the H2-PAH distance is nearly constant within MP2 theory, and independent on the size of the PAH.

- (iii) As in other weakly bound systems, as non-polar molecules or solids of noble gases, the long-range part of the interaction energy should be proportional to

, as already proposed by London.[33]

, as already proposed by London.[33]

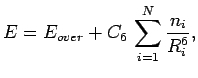

The factors (i) and (ii) suggest that there is a roughly constant part of the energy,  , and the remainder describes the dispersion interaction.

Thus if H2 is adsorbed normal to the PAH on top of a hexagonal ring,

the interaction energy can be approximated with

, and the remainder describes the dispersion interaction.

Thus if H2 is adsorbed normal to the PAH on top of a hexagonal ring,

the interaction energy can be approximated with

|

|

|

(2.1) |

where  is the number of rings in the PAH, and

is the number of rings in the PAH, and  is the number of equivalent rings which have all the same distance

is the number of equivalent rings which have all the same distance  to the molecular mass-centre of H2.

If the MP2 energies from Table 2.2 are plotted against the term

to the molecular mass-centre of H2.

If the MP2 energies from Table 2.2 are plotted against the term

(as shown in the included plot in Figure 2.5), the resulting

(as shown in the included plot in Figure 2.5), the resulting

Figure 2.5:

Interaction energy  of H

of H (in kJ

(in kJ mol

mol ) physisorbed at the central site of a

graphene platelet with radius

) physisorbed at the central site of a

graphene platelet with radius  (in Å).

The enclosed figure shows the correlation of the calculated MP2 physisorption

energies

(in Å).

The enclosed figure shows the correlation of the calculated MP2 physisorption

energies  in kJ

in kJ mol

mol with the term

with the term

(in Å

(in Å ). The constant energy

contribution

). The constant energy

contribution  and the dispersion coefficient

and the dispersion coefficient  from

Eq. (2.1) are determined by linear regression.

from

Eq. (2.1) are determined by linear regression.

|

parameters of the regression are the dispersion coefficient  kJ Å

kJ Å mol

mol and the intercept

0.52.2

and the intercept

0.52.2

kJ

kJ mol

mol , with correlation coefficient of the regression

, with correlation coefficient of the regression  .

While this correlation is not good enough to compute quantitatively the physisorption energy of PAHs with H2, it is still satisfactory

for the interpolation to graphene and to discuss the size effect of the interaction.

The E

.

While this correlation is not good enough to compute quantitatively the physisorption energy of PAHs with H2, it is still satisfactory

for the interpolation to graphene and to discuss the size effect of the interaction.

The E value, which is attributed to weakly overlapping densities, is in perfect

agreement with its determination by Tran et al. [52] and the CCSD(T) level of theory (Tab. 2.1).

Application of Eq. 2.1 to the PAHs computed in this study gives a maximum error of 0.3 kJ

value, which is attributed to weakly overlapping densities, is in perfect

agreement with its determination by Tran et al. [52] and the CCSD(T) level of theory (Tab. 2.1).

Application of Eq. 2.1 to the PAHs computed in this study gives a maximum error of 0.3 kJ mol

mol with respect to

the MP2 results.

with respect to

the MP2 results.

As shown in Figure 2.5, the dispersion interaction, and hence the total interaction, will

reach a limit for larger platelet sizes, as the number of rings  increases quadratically with the platelet radius,

while each contribution is divided by

increases quadratically with the platelet radius,

while each contribution is divided by  . Saturation is reached for PAH diameters of

. Saturation is reached for PAH diameters of  15 Å,

and the graphene-H2 interaction is only 0.8 kJ

15 Å,

and the graphene-H2 interaction is only 0.8 kJ mol

mol stronger than that of coronene with H2.

The total interaction energy for the extrapolated graphene using Eq. 2.1 thus reach a

value of 7.2 kJ

stronger than that of coronene with H2.

The total interaction energy for the extrapolated graphene using Eq. 2.1 thus reach a

value of 7.2 kJ mol

mol per H2.

This shows that for large PAHs and graphene both contributions, dispersion interaction and overlapping density,

are both very important to describe the physisorption correctly.

per H2.

This shows that for large PAHs and graphene both contributions, dispersion interaction and overlapping density,

are both very important to describe the physisorption correctly.

Lyuben Zhechkov

2007-09-04

![]() PAHs series of calculations (shown on Fig. 2.1) is the presence of a correlation between the number of the hexagonal carbon rings and the H2

PAHs series of calculations (shown on Fig. 2.1) is the presence of a correlation between the number of the hexagonal carbon rings and the H2![]() PAH interaction (see Table 2.2).

In other words the interaction grows with the number of the closely situated hexagon rings.

For the H2

PAH interaction (see Table 2.2).

In other words the interaction grows with the number of the closely situated hexagon rings.

For the H2![]() benzene complex, the physisorption energy is found to be 4.8 kJ

benzene complex, the physisorption energy is found to be 4.8 kJ![]() mol

mol![]() , while for the central ring of coronene it is 6.4 kJ

, while for the central ring of coronene it is 6.4 kJ![]() mol

mol![]() .

All other sites studied here give physisorption energies between these values.

Moreover, these series of calculations show that the interaction increases with the size of the PAH.

On the other hand, a ring situated at larger distance contributes less to the total H2

.

All other sites studied here give physisorption energies between these values.

Moreover, these series of calculations show that the interaction increases with the size of the PAH.

On the other hand, a ring situated at larger distance contributes less to the total H2![]() PAH energy interaction.

The latter effect can be clearly observed by changing the adsorption site (ring) of H2 on linear PAH molecules like naphthalene, anthracene and pentacene (see Tab. 2.2).

1.0

PAH energy interaction.

The latter effect can be clearly observed by changing the adsorption site (ring) of H2 on linear PAH molecules like naphthalene, anthracene and pentacene (see Tab. 2.2).

1.0

![]() increases quadratically with the platelet radius,

while each contribution is divided by

increases quadratically with the platelet radius,

while each contribution is divided by ![]() . Saturation is reached for PAH diameters of

. Saturation is reached for PAH diameters of ![]() 15 Å,

and the graphene-H2 interaction is only 0.8 kJ

15 Å,

and the graphene-H2 interaction is only 0.8 kJ![]() mol

mol![]() stronger than that of coronene with H2.

The total interaction energy for the extrapolated graphene using Eq. 2.1 thus reach a

value of 7.2 kJ

stronger than that of coronene with H2.

The total interaction energy for the extrapolated graphene using Eq. 2.1 thus reach a

value of 7.2 kJ![]() mol

mol![]() per H2.

This shows that for large PAHs and graphene both contributions, dispersion interaction and overlapping density,

are both very important to describe the physisorption correctly.

per H2.

This shows that for large PAHs and graphene both contributions, dispersion interaction and overlapping density,

are both very important to describe the physisorption correctly.