Real gas physisorption

The H2 H2 interactions are strongly repulsive at intermolecular distance

H2 interactions are strongly repulsive at intermolecular distance  2.5 Å[54,55].

For graphene slit pores a higher H2 guest densities are expected (

2.5 Å[54,55].

For graphene slit pores a higher H2 guest densities are expected ( 0.01 gcm

0.01 gcm ) therefore, hydrogen can no longer be treated as an ideal gas.

Although, it is possible to simulate the high-density H2-graphene system directly, for example using the grand canonical path integral Monte Carlo approach[24,61,62,63,64], such calculations are rather laborious and may be hard to interpret.

At the same time, for slowly varying potentials and low gas density, the adsorption free energy of an ideal gas is a good approximation to the adsorption free energy of the real gas.

However, at higher density the ideal gas approximation would require a correction because of the repulsion forces in the real gas.3.1The estimation of the corrections due to H2 nonideality at higher densities from an experimental equation of state [36] is made as follows:

Given the external H2 pressure

) therefore, hydrogen can no longer be treated as an ideal gas.

Although, it is possible to simulate the high-density H2-graphene system directly, for example using the grand canonical path integral Monte Carlo approach[24,61,62,63,64], such calculations are rather laborious and may be hard to interpret.

At the same time, for slowly varying potentials and low gas density, the adsorption free energy of an ideal gas is a good approximation to the adsorption free energy of the real gas.

However, at higher density the ideal gas approximation would require a correction because of the repulsion forces in the real gas.3.1The estimation of the corrections due to H2 nonideality at higher densities from an experimental equation of state [36] is made as follows:

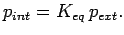

Given the external H2 pressure  , and the equilibrium constant

, and the equilibrium constant  obtained from the ideal gas simulation, the effective ``internal'' H2 pressure

obtained from the ideal gas simulation, the effective ``internal'' H2 pressure  is calculated as

is calculated as

|

|

|

(3.1) |

From  and the experimental H2 equation of state[36], the molar volume

and the experimental H2 equation of state[36], the molar volume  is obtained.

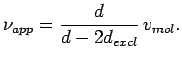

The apparent molar volume of H2, characterising volumetric efficiency of the storage system is then given by

is obtained.

The apparent molar volume of H2, characterising volumetric efficiency of the storage system is then given by

|

|

|

(3.2) |

For the dual-layer systems, the mass fraction of H2 in the H2-graphene system is given by

|

|

|

(3.3) |

where  is in

is in

and

and  ,

,  are in Å.

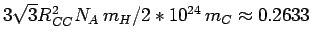

The structural prefactor

are in Å.

The structural prefactor

Å

Å is calculated from the fixed in-plane carbon

is calculated from the fixed in-plane carbon carbon distance

carbon distance  , the atomic masses

, the atomic masses  and

and  of hydrogen and carbon, and the Avogadro constant

of hydrogen and carbon, and the Avogadro constant  . Calculated internal pressure, volumetric

and mass weight densities for representative temperatures, and

external H2 pressures are collected in Table 3.2 and Fig. 3.2.

. Calculated internal pressure, volumetric

and mass weight densities for representative temperatures, and

external H2 pressures are collected in Table 3.2 and Fig. 3.2.

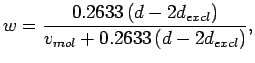

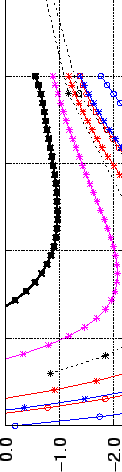

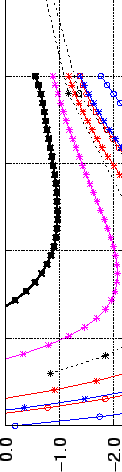

Figure:

Gravimetric (Left) and volumetric (Right) H2 storage capacities of

layered graphene structures, calculated from the real gas equation of state, as

functions of the interlayer separation (see Table 3.2 and text). The targets

for automotive applications [4] (Gwt=6.0%,  cm

cm mol

mol ) are indicated by

solid horizontal lines. The pressure (P) and the temperature (T) are given respectively in MPa and K.

) are indicated by

solid horizontal lines. The pressure (P) and the temperature (T) are given respectively in MPa and K.

|

The procedure outlined above is equivalent to treating graphene structure as a ``nanopump'', increasing the hydrogen pressure inside the structure, but otherwise leaving H2 guest gas unaffected.

Although approximate, this treatment allows to completely sidestep the question of the choice of H2 H2 interaction potentials, treatment of the quantum effects for H2

H2 interaction potentials, treatment of the quantum effects for H2 H2 interactions, and the associated convergence issues.

It is important to understand the approximations made in the nonideal gas estimation of the storage capacities

H2 interactions, and the associated convergence issues.

It is important to understand the approximations made in the nonideal gas estimation of the storage capacities  and

and  . Eq. 3.1 requires the use of fugacities

. Eq. 3.1 requires the use of fugacities  , rather than gas pressures

, rather than gas pressures  .

As the

.

As the  ratio decreases with pressure (at temperatures and pressures considered presently), Eq. 3.1 is expected to underestimate the internal pressure

ratio decreases with pressure (at temperatures and pressures considered presently), Eq. 3.1 is expected to underestimate the internal pressure  .

At the same time, using the free gas equation of state to calculate the molar volume neglects changes in H2

.

At the same time, using the free gas equation of state to calculate the molar volume neglects changes in H2 H2 radial distribution function due to the adsorption potential and, thus, overestimates the compressibility of the guest.

Although these two defects may be expected to partially offset each other, the overall nonideality correction is at best semiquantitative.

To illustrate the effect of the nonideality corrections, Table 3.2 also includes

H2 radial distribution function due to the adsorption potential and, thus, overestimates the compressibility of the guest.

Although these two defects may be expected to partially offset each other, the overall nonideality correction is at best semiquantitative.

To illustrate the effect of the nonideality corrections, Table 3.2 also includes  and

and  values calculated from the ideal gas equation of state.

When the real and ideal gas values are close, the residual error in the storage capacity is determined by the remaining uncertainties in the ab initio H2

values calculated from the ideal gas equation of state.

When the real and ideal gas values are close, the residual error in the storage capacity is determined by the remaining uncertainties in the ab initio H2 graphene interaction potential and the corresponding

graphene interaction potential and the corresponding  fit.

Based on the basis set and method convergence, the estimation of the error is about

fit.

Based on the basis set and method convergence, the estimation of the error is about  25 % in

25 % in  and

and  .

When the real and ideal gas values deviate significantly from each other, the real gas result is clearly more reliable but should still be treated only as a semiquantitative estimate.

The spatial distribution of molecular hydrogen adsorbed on graphene is very delocalised (see Fig. 3.3).

.

When the real and ideal gas values deviate significantly from each other, the real gas result is clearly more reliable but should still be treated only as a semiquantitative estimate.

The spatial distribution of molecular hydrogen adsorbed on graphene is very delocalised (see Fig. 3.3).

Figure:

Probability densities for selected lowest eigenstates of the translational

nuclear Hamiltonian. The lowest in-phase (Left to Right: first and second)

eigenstates for the double-layer structure are shown ( = 8 Å).

= 8 Å).

|

This observation is in agreement with previous path-integral and Monte Carlo simulations [22,65,62] and indicates an essentially free lateral motion of H2.

The calculations described hereby indicate a slightly attractive (-1.2 kJ mol

mol ) H2

) H2 graphene free reaction energy at 300 K (see Table 3.3), mainly because of the entropic contribution (

graphene free reaction energy at 300 K (see Table 3.3), mainly because of the entropic contribution (

)

)

to the free energy which is significant.

The physisorption free energy corresponds to an equilibrium constant of  =exp(

=exp(

.

In other words, at room temperature a graphene surface increases the H2 abundance by only

.

In other words, at room temperature a graphene surface increases the H2 abundance by only  60 % when an increase of at least 700 times is necessary in order to make the storage density of H2 enough for conventional usage [2].

The enhancement factor however, does not significantly change at lower temperatures (Fig. 3.4) or higher pressures.

Considering the volume taken up by graphene itself, graphene surfaces are unsuitable for practical H2 storage.

60 % when an increase of at least 700 times is necessary in order to make the storage density of H2 enough for conventional usage [2].

The enhancement factor however, does not significantly change at lower temperatures (Fig. 3.4) or higher pressures.

Considering the volume taken up by graphene itself, graphene surfaces are unsuitable for practical H2 storage.

Figure:

Equilibrium constants  (Left) and reaction free energies

(Left) and reaction free energies

(Right) are plotted in kJ

(Right) are plotted in kJ mol

mol as a function of the temperature at interlayer distance d = 8 Å.

as a function of the temperature at interlayer distance d = 8 Å.

|

To improve the binding capacity, it is possible to sandwich H2 between graphene layers.

Binding energies of up to 30 kJ mol

mol have been reported for H2 inside carbon nanotube tips [53].

The calculated hereby quantum-mechanical physisorption free energies are for interlayer distances (

have been reported for H2 inside carbon nanotube tips [53].

The calculated hereby quantum-mechanical physisorption free energies are for interlayer distances ( ), between two graphene layers ranging from 4 to 14 Å.

As can be seen from the results in Table 3.3, at separations above 7 Å the zero-temperature enthalpy of the H2

), between two graphene layers ranging from 4 to 14 Å.

As can be seen from the results in Table 3.3, at separations above 7 Å the zero-temperature enthalpy of the H2 graphene interaction is very similar for bi- and monolayer structures [52].

Even at these separations, the free energy is strongly affected by the presence and position of the second layer (Table 3.3 and Fig. 3.5).

graphene interaction is very similar for bi- and monolayer structures [52].

Even at these separations, the free energy is strongly affected by the presence and position of the second layer (Table 3.3 and Fig. 3.5).

Figure:

Equilibrium constants  (Left) and reaction free energies

(Left) and reaction free energies

(Right) are plotted in kJ

(Right) are plotted in kJ mol

mol as a function of the interlayer distance at temperature T = 300 K.

as a function of the interlayer distance at temperature T = 300 K.

|

The simulations predict an increase in H2 binding free energy with decreasing layer separation up to a maximum of  10 kJ

10 kJ mol

mol for an interlayer distance of

for an interlayer distance of  6 Å.

For smaller separations, the exchange repulsion reduces the free energy considerably (Fig. 3.5), which becomes positive for interlayer separations

6 Å.

For smaller separations, the exchange repulsion reduces the free energy considerably (Fig. 3.5), which becomes positive for interlayer separations  5 Å.

The thermodynamics of the H2

5 Å.

The thermodynamics of the H2 graphene system at shorter separations is purely repulsive [66].

The calculated equilibrium constant shows a sharp ``peak'' at 6

graphene system at shorter separations is purely repulsive [66].

The calculated equilibrium constant shows a sharp ``peak'' at 6 7 Å (Fig. 3.2 Left).

Consequently, experimental fine-tuning of

7 Å (Fig. 3.2 Left).

Consequently, experimental fine-tuning of  should be taken with care; too small separation could readily lead to a collapse in the adsorption free energy.

At ambient conditions (

should be taken with care; too small separation could readily lead to a collapse in the adsorption free energy.

At ambient conditions ( K,

K,  MPa) the maximum estimate of the present calculations is for equilibrium constant of

MPa) the maximum estimate of the present calculations is for equilibrium constant of  30 for a graphene

30 for a graphene graphene interlayer distance of 7 Å.

The very favourable adsorption free energies for

graphene interlayer distance of 7 Å.

The very favourable adsorption free energies for  6

6 7 Å effectively creates a ``nanopump'', increasing the internal H2 pressure inside the layered structure (see Table 3.2).

As a result, the target of 62 kg/m

7 Å effectively creates a ``nanopump'', increasing the internal H2 pressure inside the layered structure (see Table 3.2).

As a result, the target of 62 kg/m (

( 31 cm

31 cm /mol

/mol ) volumetric storage density, set by the FCVT[4], can be approached at a moderate external H2 pressure (

) volumetric storage density, set by the FCVT[4], can be approached at a moderate external H2 pressure ( 10 MPa) even at room temperature.

At the same time, the simulations indicate that a pure carbon based (graphene or graphite

10 MPa) even at room temperature.

At the same time, the simulations indicate that a pure carbon based (graphene or graphite  like) storage system cannot achieve the FCVT Project[4] gravimetric storage target (6.0 wt % H2) at room temperature and moderate pressures (up to 10 MPa).

like) storage system cannot achieve the FCVT Project[4] gravimetric storage target (6.0 wt % H2) at room temperature and moderate pressures (up to 10 MPa).

Due to the increasingly nonideal behaviour of H2 at high internal pressures, room-temperature storage capacity of these hypothetical systems is limited to 2 3 wt % at 5 MPa, and to 3

3 wt % at 5 MPa, and to 3 4 wt % at 10 MPa.

Although not yet achieving the FCVT[4] target, this storage capacity is already competitive with best known physisorption substrates.

Similar room-temperature gravimetric storage capacities have been calculated for a wide range of interlayer spacing (

4 wt % at 10 MPa.

Although not yet achieving the FCVT[4] target, this storage capacity is already competitive with best known physisorption substrates.

Similar room-temperature gravimetric storage capacities have been calculated for a wide range of interlayer spacing ( 7

7 12 Å; see Fig. 3.2), which should simplify practical design of the storage material.

12 Å; see Fig. 3.2), which should simplify practical design of the storage material.

Caution should be applied in interpreting the results of the simulations concerning small interlayer distances ( 9 Å).

At low pressures, van der Waals close-packing arguments suggest that at most two H2 monolayers (6.6 wt %) can fit between the graphene layers separated by

9 Å).

At low pressures, van der Waals close-packing arguments suggest that at most two H2 monolayers (6.6 wt %) can fit between the graphene layers separated by  = 9 Å.

For

= 9 Å.

For  = 6 Å, just one monolayer can fit in the structure, indicating a maximum H2 storage capacity of 3.3 wt %.

Although this argument holds at low pressures, the large adsorption free energy calculated for small interlayer spacing can drive the internal pressure beyond 2 kbar (1 bar = 100 kPa), even at moderate external pressures (Table 3.2).

In the free hydrogen gas, the density at such pressures exceeds the close-packing limit for hydrogen gas [36].

At the same time, the approach to H2

= 6 Å, just one monolayer can fit in the structure, indicating a maximum H2 storage capacity of 3.3 wt %.

Although this argument holds at low pressures, the large adsorption free energy calculated for small interlayer spacing can drive the internal pressure beyond 2 kbar (1 bar = 100 kPa), even at moderate external pressures (Table 3.2).

In the free hydrogen gas, the density at such pressures exceeds the close-packing limit for hydrogen gas [36].

At the same time, the approach to H2 H2 interactions is crude, so that the pronounced maximum in H2 storage capacity found at interlayer spacing 6 Å

H2 interactions is crude, so that the pronounced maximum in H2 storage capacity found at interlayer spacing 6 Å

7.5 Å should be considered only as a tantalising possibility.

Confirming or disproving its existence would require further, more elaborate simulations or experiments.

7.5 Å should be considered only as a tantalising possibility.

Confirming or disproving its existence would require further, more elaborate simulations or experiments.

The qualitative difference in the H2 storage capacity of mono- and bilayer graphene is easily understood by comparing the density of states (DOS) in Fig. 3.6

Figure:

Density of states of free H2 gas (empty box) and H2 in an

external potential. (Left) Adsorption on graphene surface. (Right) Adsorption between two graphene layers at 8 Å distance.

|

for the two models.

The single-layer graphene potential creates relatively few H2 bound states, which are localised at the graphene surface.

For the majority of states, the DOS is very similar to the DOS of free H2, reflecting the short-range nature of the binding potential.

For the double-layer structure, DOS has many binding states, with the bulk of the available states shifted to low energies.

In other words, whereas free H2 can move away from a single layer and hence on average experiences little attraction, H2 inside a double-layer structure is always in an attractive potential.

Figure 3.3 shows probability densities of H2 in between two graphene layers, for a few lowest states.

Even low-energy modes are delocalised on the surface.

The abundance of low-energy surface modes on graphene and in sandwiched structures suggests the presence of a two-dimensional H2 gas.

The lateral modes should facilitate diffusion inside the storage material, thus ensuring easy loading and unloading.

The estimated limit of accuracy of these calculations at  8 Å is within

8 Å is within  25 % (see Chapter 1).

Even considering this large margin of error, the conclusion is that an H2 storage enhancement material approaching, or possibly even exceeding, the FCVT[4] specification can be produced by encapsulating molecular hydrogen in graphene layers with an appropriate interlayer spacing.

The significant dependence of the equilibrium constant on the graphene interlayer distance indicates that the H2 abundance of a nanostructured graphene system is intimately controlled by the nano- and mesoscopic structure.

Together with the pronounced temperature dependency, the controversial issue of the qualitatively different amounts of H2 adsorption in the literature of the last decade [65,67,68,69,70] on graphene systems may well arise from slight microstructural variations both within and between different samples.

25 % (see Chapter 1).

Even considering this large margin of error, the conclusion is that an H2 storage enhancement material approaching, or possibly even exceeding, the FCVT[4] specification can be produced by encapsulating molecular hydrogen in graphene layers with an appropriate interlayer spacing.

The significant dependence of the equilibrium constant on the graphene interlayer distance indicates that the H2 abundance of a nanostructured graphene system is intimately controlled by the nano- and mesoscopic structure.

Together with the pronounced temperature dependency, the controversial issue of the qualitatively different amounts of H2 adsorption in the literature of the last decade [65,67,68,69,70] on graphene systems may well arise from slight microstructural variations both within and between different samples.

It is hence an experimental challenge to provide a synthesis of nanostructured graphene with sufficiently uniform and reproducible interlayer distances suitable for H2 storage.

One possibility is to introduce well defined spacers[22].

Aside from the tuning possibilities, the spacers may provide additional benefits, such as an increase in the stability of the storage media.

Spacers can also act as molecular sieves, preventing penetration of larger gas molecules such as N2, CO, and CO2, which typically have a higher graphene binding energy than H2 and may reduce storage capacity [71].

For example, the computed binding energy of N2 benzene model system is two times larger than the comparable H2

benzene model system is two times larger than the comparable H2 benzene model[72].

benzene model[72].

Lyuben Zhechkov

2007-09-04

![]() 3 wt % at 5 MPa, and to 3

3 wt % at 5 MPa, and to 3![]() 4 wt % at 10 MPa.

Although not yet achieving the FCVT[4] target, this storage capacity is already competitive with best known physisorption substrates.

Similar room-temperature gravimetric storage capacities have been calculated for a wide range of interlayer spacing (

4 wt % at 10 MPa.

Although not yet achieving the FCVT[4] target, this storage capacity is already competitive with best known physisorption substrates.

Similar room-temperature gravimetric storage capacities have been calculated for a wide range of interlayer spacing (![]() 7

7![]() 12 Å; see Fig. 3.2), which should simplify practical design of the storage material.

12 Å; see Fig. 3.2), which should simplify practical design of the storage material.

![]() 9 Å).

At low pressures, van der Waals close-packing arguments suggest that at most two H2 monolayers (6.6 wt %) can fit between the graphene layers separated by

9 Å).

At low pressures, van der Waals close-packing arguments suggest that at most two H2 monolayers (6.6 wt %) can fit between the graphene layers separated by ![]() = 9 Å.

For

= 9 Å.

For ![]() = 6 Å, just one monolayer can fit in the structure, indicating a maximum H2 storage capacity of 3.3 wt %.

Although this argument holds at low pressures, the large adsorption free energy calculated for small interlayer spacing can drive the internal pressure beyond 2 kbar (1 bar = 100 kPa), even at moderate external pressures (Table 3.2).

In the free hydrogen gas, the density at such pressures exceeds the close-packing limit for hydrogen gas [36].

At the same time, the approach to H2

= 6 Å, just one monolayer can fit in the structure, indicating a maximum H2 storage capacity of 3.3 wt %.

Although this argument holds at low pressures, the large adsorption free energy calculated for small interlayer spacing can drive the internal pressure beyond 2 kbar (1 bar = 100 kPa), even at moderate external pressures (Table 3.2).

In the free hydrogen gas, the density at such pressures exceeds the close-packing limit for hydrogen gas [36].

At the same time, the approach to H2![]() H2 interactions is crude, so that the pronounced maximum in H2 storage capacity found at interlayer spacing 6 Å

H2 interactions is crude, so that the pronounced maximum in H2 storage capacity found at interlayer spacing 6 Å ![]()

![]()

![]() 7.5 Å should be considered only as a tantalising possibility.

Confirming or disproving its existence would require further, more elaborate simulations or experiments.

7.5 Å should be considered only as a tantalising possibility.

Confirming or disproving its existence would require further, more elaborate simulations or experiments.

![]() 8 Å is within

8 Å is within ![]() 25 % (see Chapter 1).

Even considering this large margin of error, the conclusion is that an H2 storage enhancement material approaching, or possibly even exceeding, the FCVT[4] specification can be produced by encapsulating molecular hydrogen in graphene layers with an appropriate interlayer spacing.

The significant dependence of the equilibrium constant on the graphene interlayer distance indicates that the H2 abundance of a nanostructured graphene system is intimately controlled by the nano- and mesoscopic structure.

Together with the pronounced temperature dependency, the controversial issue of the qualitatively different amounts of H2 adsorption in the literature of the last decade [65,67,68,69,70] on graphene systems may well arise from slight microstructural variations both within and between different samples.

25 % (see Chapter 1).

Even considering this large margin of error, the conclusion is that an H2 storage enhancement material approaching, or possibly even exceeding, the FCVT[4] specification can be produced by encapsulating molecular hydrogen in graphene layers with an appropriate interlayer spacing.

The significant dependence of the equilibrium constant on the graphene interlayer distance indicates that the H2 abundance of a nanostructured graphene system is intimately controlled by the nano- and mesoscopic structure.

Together with the pronounced temperature dependency, the controversial issue of the qualitatively different amounts of H2 adsorption in the literature of the last decade [65,67,68,69,70] on graphene systems may well arise from slight microstructural variations both within and between different samples.

![]() benzene model system is two times larger than the comparable H2

benzene model system is two times larger than the comparable H2![]() benzene model[72].

benzene model[72].