Bundles of nanotubes

A model of bundle, nanotubes with close packaging hexagonal arrangement, has been used to assess the adsorbing capabilities of the outer nanotube surface.

The contribution of the nanotube interstitial space can be deduced by comparison with the data already available in the previous section.

The simulation is carried out so that it does not consider the boundary effects of the ropes, i.e. the model is infinitely large.

As explained later in the chapter, in the case of comparison with experimental data this assumption may lead to confusions.

However, the model is build on the purpose to deduce the most important factors, which influence the H2-storage capacity of the carbon media.

Since the distance between the nanotube walls in a bundle is fixed to 3.41 Å (the graphene graphene interlayer distance in graphite), the interstitial channels in a bundle depend only on the radius of the tube.

Each of these channels is surrounded by tree nanotubes and creates an interstice with negatively bent walls.

As noticed by Okamoto and Miyamoto [53] in comparison with the concave surface, the convex carbon surfaces notably manifest a weaker attraction for the hydrogen molecules.

This effect is demonstrated on Figure 5.6, where the inside and outside interaction potentials are plotted against the radius of the nanotube's core.

graphene interlayer distance in graphite), the interstitial channels in a bundle depend only on the radius of the tube.

Each of these channels is surrounded by tree nanotubes and creates an interstice with negatively bent walls.

As noticed by Okamoto and Miyamoto [53] in comparison with the concave surface, the convex carbon surfaces notably manifest a weaker attraction for the hydrogen molecules.

This effect is demonstrated on Figure 5.6, where the inside and outside interaction potentials are plotted against the radius of the nanotube's core.

Figure:

Maxima in the inside and outside interaction potentials of H2 with nanotubes having radius  (Left).

The nested plot shows the correlation between the radius of nanotubes and radius of intertubular channels. Nantubes with different chirality are given with appropriate symbols. Schematic representation of the interstice confined by 3 nanotubes is given on the Right. All length units are in Å.

(Left).

The nested plot shows the correlation between the radius of nanotubes and radius of intertubular channels. Nantubes with different chirality are given with appropriate symbols. Schematic representation of the interstice confined by 3 nanotubes is given on the Right. All length units are in Å.

|

Both the interior and the interstitial channels reach maximum potential well depths at nearly the same cavity diameters ( 3 Å).

The nested plot on Fig. 5.6 shows the relation between the radius of different cavity types in the bundle.

Besides the negative curvature, the interstitial channels with very small diameters have particular topology.

This is caused by the undulations on the nanotube's wall, which are characteristic for nanotubes with small radius.

As a consequence, oscillations in the potential and attractive values have been found for interstitial channels with radius less than 2.5 Å (corresponds to bundles consisting of nanotubes with radius of 3.1 Å, see the nested plot in Fig. 5.6).

Both characteristics of the model produce a 3D potential in the interstitial channels with shape similar to a bulb condenser.

This effectively creates space ``pockets" between the nanotubes where the volume is enough to avoid the repulsion area of the potential.

These attractive regions emerge also as a consequence of the non-optimised mutual position of nanotubes in the bundle.

However, channels with radius

3 Å).

The nested plot on Fig. 5.6 shows the relation between the radius of different cavity types in the bundle.

Besides the negative curvature, the interstitial channels with very small diameters have particular topology.

This is caused by the undulations on the nanotube's wall, which are characteristic for nanotubes with small radius.

As a consequence, oscillations in the potential and attractive values have been found for interstitial channels with radius less than 2.5 Å (corresponds to bundles consisting of nanotubes with radius of 3.1 Å, see the nested plot in Fig. 5.6).

Both characteristics of the model produce a 3D potential in the interstitial channels with shape similar to a bulb condenser.

This effectively creates space ``pockets" between the nanotubes where the volume is enough to avoid the repulsion area of the potential.

These attractive regions emerge also as a consequence of the non-optimised mutual position of nanotubes in the bundle.

However, channels with radius  3 Å are expected to reduce the diffusion coefficient of molecular hydrogen [86] into the material and thus prevent the absorption processes in the bundle interstitial space.

Hence, the calculated values for the H2 storage capacities concerning structures with channel radius

3 Å are expected to reduce the diffusion coefficient of molecular hydrogen [86] into the material and thus prevent the absorption processes in the bundle interstitial space.

Hence, the calculated values for the H2 storage capacities concerning structures with channel radius  3 Å should not be considered as realistic and should be interpreted with care when dealing with practical applications.

3 Å should not be considered as realistic and should be interpreted with care when dealing with practical applications.

At 300 K and 5 MPa the bundles exercise almost twice the estimated storage capacities considered for the core of single nanotubes. However, the volumetric capacities at given temperature and pressure are nearly the same.

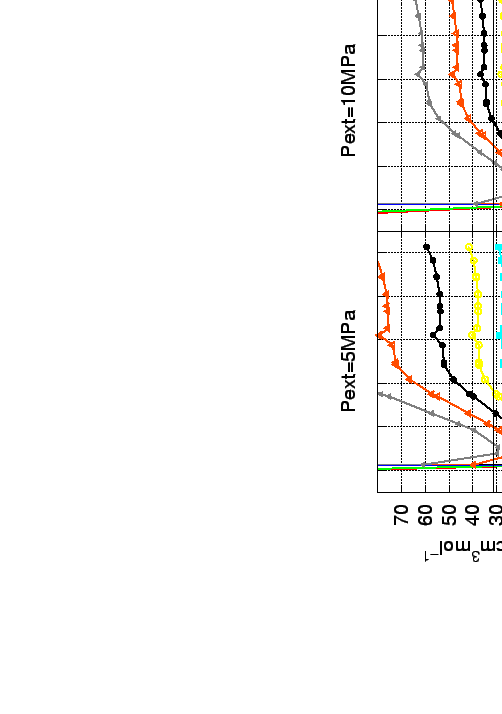

The volumetric and mass ratio for representative temperatures and external H2 pressures are collected in Figure 5.7 and the corresponding interaction free energy and equilibrium constants on Fig. 5.8.

Figure:

Volumetric (Top) and gravimetric (Bottom) storage capacities for

bundle of nanotubes with radius  are given for various temperatures (see the legend). Left and right columns give the values

respectively for pressures at 5 and 10 MPa.

The symbols on the curves denote that the approximation is within the limits (pressure and temperature) of the real gas equation of state [36].

The targets[4] for automotive applications (Gwt) 6.0 %,(V) 44.4 cm

are given for various temperatures (see the legend). Left and right columns give the values

respectively for pressures at 5 and 10 MPa.

The symbols on the curves denote that the approximation is within the limits (pressure and temperature) of the real gas equation of state [36].

The targets[4] for automotive applications (Gwt) 6.0 %,(V) 44.4 cm /mol) are indicated as horizontal lines.

/mol) are indicated as horizontal lines.

|

The simulations suggest that both systems (for single nanotube and bundle) will increase the H2 abundance to nearly the same gas density, while the mass fraction of hydrogen molecules in the bundle is twice larger.

Another characteristic property of the bundles is that, unlike for single nanotubes, there are two maxima (especially at low temperatures) in the curves for the gravimetric and the volumetric capacities (see 5.7).

The first one appears in the region of nanotubes with radius of  3.5 Å, the second one appears for diameters in the range of 7-8 Å.

If the curves for the gravimetric and the volumetric capacities are superimposed with the curves for the interaction potential, it can be clearly seen that the second maximum appears for bundles where the strongest interactions are found to be in the interstitial channels, i.e. channels with a radius

3.5 Å, the second one appears for diameters in the range of 7-8 Å.

If the curves for the gravimetric and the volumetric capacities are superimposed with the curves for the interaction potential, it can be clearly seen that the second maximum appears for bundles where the strongest interactions are found to be in the interstitial channels, i.e. channels with a radius  3 Å.

However, according to the nested plot in Fig. 5.6 and ref. Y.M.2002, the bundles with interstitial space with radius smaller than 3 Å should be considered as impenetrable for hydrogen molecules.

Therefore, as a more realistic models for bundle of nanotubes are suggested those with radius greather than 6 Å (see nested plot on Fig. 5.6).

The ability, of both the interstitial and core nanotube sites (bundles consisting of nanotubes with radius 6-8 Å), to accommodate a reasonable amount of hydrogen gas leads to a plateau in the volumetric and gravimetric capacities.

As already suggested from Fig. 5.1, the core potential of nanotube with large diameter (

3 Å.

However, according to the nested plot in Fig. 5.6 and ref. Y.M.2002, the bundles with interstitial space with radius smaller than 3 Å should be considered as impenetrable for hydrogen molecules.

Therefore, as a more realistic models for bundle of nanotubes are suggested those with radius greather than 6 Å (see nested plot on Fig. 5.6).

The ability, of both the interstitial and core nanotube sites (bundles consisting of nanotubes with radius 6-8 Å), to accommodate a reasonable amount of hydrogen gas leads to a plateau in the volumetric and gravimetric capacities.

As already suggested from Fig. 5.1, the core potential of nanotube with large diameter ( 14 Å) mimics the graphene sheet model.

Therefore, it is expected that, in such systems, H2 molecules have higher density in the bundle's interstitial space, while for the interior of the nanotube the highest molecule density is located in the vicinity of the nanotube wall.

However, further enlarging of the nanotube radius (

14 Å) mimics the graphene sheet model.

Therefore, it is expected that, in such systems, H2 molecules have higher density in the bundle's interstitial space, while for the interior of the nanotube the highest molecule density is located in the vicinity of the nanotube wall.

However, further enlarging of the nanotube radius ( 14 Å) will lead to interstitial cavities with diameter larger then 10 Å, where both the interstices and the nanotube cores will mimic the graphene sheet model.

14 Å) will lead to interstitial cavities with diameter larger then 10 Å, where both the interstices and the nanotube cores will mimic the graphene sheet model.

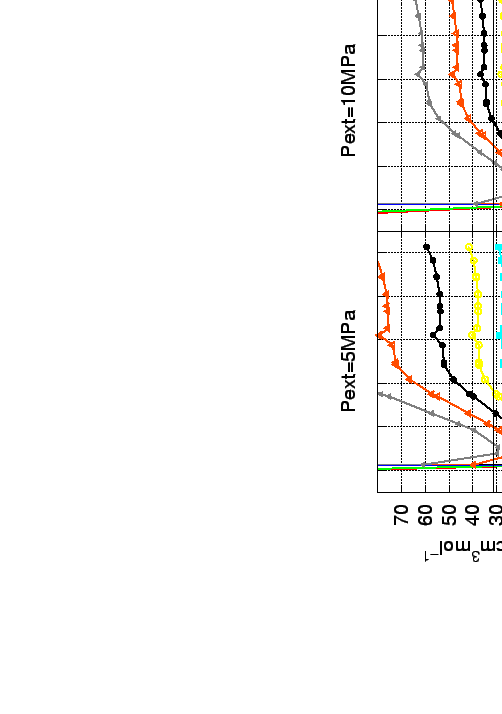

Figure:

Equilibrium constants  (Left) and reaction free energies

(Left) and reaction free energies

(Right) are plotted in kJ

(Right) are plotted in kJ mol

mol as a function of the tube radius in a bundle at different temperatures in [K]

(see the legend).

as a function of the tube radius in a bundle at different temperatures in [K]

(see the legend).

|

The simulation of the bundle and nanotube models demonstrates the bigger sorption abilities of the concave surfaces.

However, it suggests also the weaker attractive capabilities of the convex surfaces.

Since the curvatures on the bundle boundaries are bent negatively, the outer surface of the rope is suggested to physisorb hydrogen molecules more ineffectively even than the graphene sheet.

As a consequence, this results to a dramatic decrease in the gravimetric storage capacities of the bundles.

This effect has been nicely demonstrated by Williams and Eklund [64].

They define first the total endohedral (innertubular) surface, interstitial (intertubular) and the external rope surface for bundle of nanotubes with 13.6 Å and tube-tube distance of 3.2 Å.

The interaction potential values are in reasonable agreement with the ones presented hereby.

However, they show that the increase of the outer surface of the rope leads to a decrease of the H2 gravimetric storage capacity of the material.

In other words, the total mass of carbon atoms (situated mainly on the outer surface of the bundle) attracting inefficiently hydrogen molecules increases.

Lyuben Zhechkov

2007-09-04