Next: Graphite and fullerene modifications Up: SWCNTs and Carbon foams Previous: Bundles of nanotubes Contents

It has been demonstrated so far that ![]() based carbon materials (consisting entirely of carbon atoms with

based carbon materials (consisting entirely of carbon atoms with ![]() hybridisation) have the potential to store a reasonable amounts of hydrogen gas.

However, it was found that the ability of the material to accommodate a certain amount of H2 molecules depends strongly on the width and the shape of the pores (see Chapter 3.2 and 5.1).

The hereby used simulation suggests also, that pores confined in the interior of a nanotube with diameters of 7-10 Å would be good sites for hydrogen physisorption.

On the other hand, the outer surface of the tube is an ineffective adsorption site (as explained at the end of the previous chapter) and makes the material inefficient for practical application.

The experimentally detected CIG material shows reasonable gravimetric storage capacities at moderate conditions (see Chapter 4). Though the gravimetric capacities are comparable, the carbon density in CIG is about 4.5 times higher, in comparison to the one in the hypothetical graphite with interlayer distance of 8 Å (Fig 4.3 and 3.2).

Thus, a reasonable question would be if it is possible to model and synthesise well defined periodic graphite-like structure, which combines low carbon density with pores or channels appropriate for hydrogen physisorption.

Indeed, models for such of carbon materials have been proposed originally by Karfunkel et al. and Balaban et al. in their theoretical works [87,88].

hybridisation) have the potential to store a reasonable amounts of hydrogen gas.

However, it was found that the ability of the material to accommodate a certain amount of H2 molecules depends strongly on the width and the shape of the pores (see Chapter 3.2 and 5.1).

The hereby used simulation suggests also, that pores confined in the interior of a nanotube with diameters of 7-10 Å would be good sites for hydrogen physisorption.

On the other hand, the outer surface of the tube is an ineffective adsorption site (as explained at the end of the previous chapter) and makes the material inefficient for practical application.

The experimentally detected CIG material shows reasonable gravimetric storage capacities at moderate conditions (see Chapter 4). Though the gravimetric capacities are comparable, the carbon density in CIG is about 4.5 times higher, in comparison to the one in the hypothetical graphite with interlayer distance of 8 Å (Fig 4.3 and 3.2).

Thus, a reasonable question would be if it is possible to model and synthesise well defined periodic graphite-like structure, which combines low carbon density with pores or channels appropriate for hydrogen physisorption.

Indeed, models for such of carbon materials have been proposed originally by Karfunkel et al. and Balaban et al. in their theoretical works [87,88].

For the sake of simplicity the discussed structures include only the highest symmetry carbon foams e.g. their interconnected graphene segments have always nearly the same size0.55.3. This way, the width of carbon foam pores can be approximated to a cylinder with diameter the distance between the two opposite walls of the channel, thus a comparison with the nanotube models is easier.

The unit cell parameters used in the simulations have been taken from recent investigation on that topic [90].

The contribution to the potential in the simulated box has been taken from the 15 adjacent unit cells (by 15 on the left and right hand) along the channel axis and by 5 in the other two directions0.55.4.

The contribution of the ![]() carbon atoms to the total interaction potentials has been calculated in two ways since they are expected to have weaker H2 attractive capabilities0.55.5.

In the first case their contributions have been completely neglected, while in the second one the assigned interaction potential was the same as for the other

carbon atoms to the total interaction potentials has been calculated in two ways since they are expected to have weaker H2 attractive capabilities0.55.5.

In the first case their contributions have been completely neglected, while in the second one the assigned interaction potential was the same as for the other ![]() carbon atoms.

However, it has been found that this does not change sensibly neither the potential energy surface, nor affect the convergence of the equilibrium constant.

Therefore, the contributions from the C

carbon atoms.

However, it has been found that this does not change sensibly neither the potential energy surface, nor affect the convergence of the equilibrium constant.

Therefore, the contributions from the C![]() atoms have been taken as if they were C

atoms have been taken as if they were C![]() atoms.

atoms.

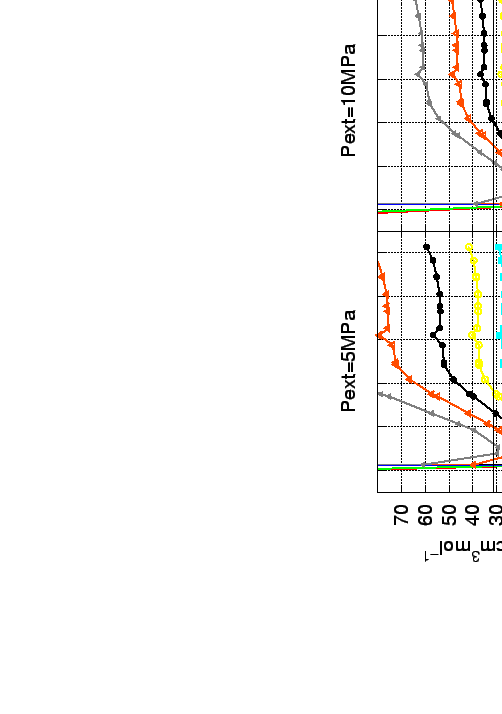

A comparison between the potential energy surfaces of nanotube cores and carbon foam pores with respect to the radius of their channels shows similar values in the potential well depth Fig. 5.10.

The figure shows two carbon foam structures, which differ from each other by the width of their pores i.e. the number of hexagon rings perpendicular to the channel axis.

Since the radius increases with the number of rings the potential in the middle of the cavity becomes weaker (similarly to nanotube's potential).

However, the coordination and the bond angles of the ![]() carbon atoms remain the same.

The contribution to the interaction potential in the regions of the

carbon atoms remain the same.

The contribution to the interaction potential in the regions of the ![]() carbon atoms is given by the overlapping potentials of atoms located around the corners.

Since the enlargement of the cavity do not influence the geometry and the number of C

carbon atoms is given by the overlapping potentials of atoms located around the corners.

Since the enlargement of the cavity do not influence the geometry and the number of C![]() atoms in the vicinity of the corners, the interaction potential on these sites is constant.

This constant interaction potential emerges as tiny cones in the corners of the hexagons as demonstrated on Fig. 5.11 (Right).

atoms in the vicinity of the corners, the interaction potential on these sites is constant.

This constant interaction potential emerges as tiny cones in the corners of the hexagons as demonstrated on Fig. 5.11 (Right).

Beside this particular characteristic of the carbon foams they closely mimic the gravimetric storage capacity of nanotubes even for relatively large pore size (Fig. 5.7 and 5.12).

|

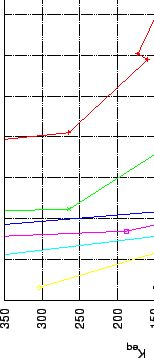

The H2 density in the material, is a function of the ``internal'' pressure (![]() ) at temperature T.

It is related to the equilibrium constant

) at temperature T.

It is related to the equilibrium constant ![]() (at the same temperature) with Eq. 3.1, which gives the increase of the pressure with respect to the one outside of the material.

Hence, the ``internal'' pressure is a direct indication for the abilities of the material to naturally compress hydrogen gas.

Respectively

(at the same temperature) with Eq. 3.1, which gives the increase of the pressure with respect to the one outside of the material.

Hence, the ``internal'' pressure is a direct indication for the abilities of the material to naturally compress hydrogen gas.

Respectively ![]() gives the strength of H2

gives the strength of H2![]() material binding.

Figures 3.4, 5.8 and 5.13 represent

material binding.

Figures 3.4, 5.8 and 5.13 represent ![]() and

and ![]() values for

values for

|